Black Sheep School of Cheesemaking's Mason Jar Saint Marcellin

"Mom. These soft mold wrinkles are just so beautiful! This is definitely the most beautiful cheese we have made."

I love Wyatt's perspective on mold. Some mold really is stunning. But to be honest, before I got into fermenting, I held my nose and flung into the compost bin whatever I found decomposing in the back of the crisper. These days, though, we spend a lot of time examining mold. Sometimes, food spoils in spectacular fashion, like when it grows "cat's hair mold." And other times, when we manage to harness the microbes we want, we get beautiful cheese.

I haven't written about cheese in awhile, but we have been working steadily behind the scenes. Over a month ago (on November 21, actually) we started making Mason Jar Saint Marcellin. Saint Marcellin cheese is from Lyon, France, and is traditionally made in little clay pots. It is a rare aged lactic cheese made with cow's milk. In The Art of Natural Cheesemaking, David Asher explains how to make Saint Marcellin in shorty mason jars. The jar itself provides the ideal aging environment for the cheese, so you don't need a cheese cave. Mason Jar Saint Marcellin seemed like the perfect cheese for us to try while we waited for the weather to cool off enough to set up our cheese cave in the garage.

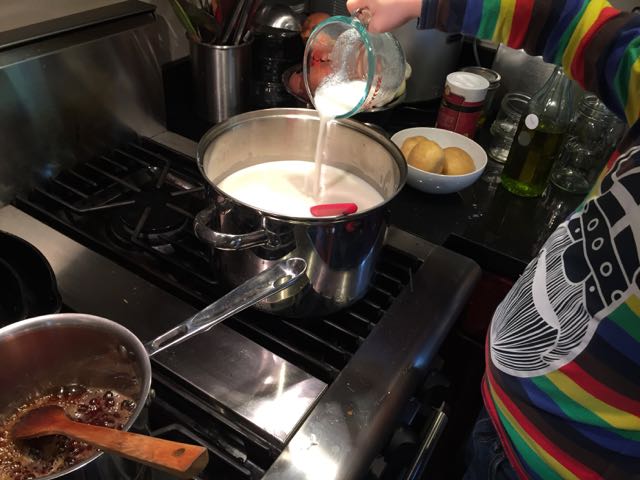

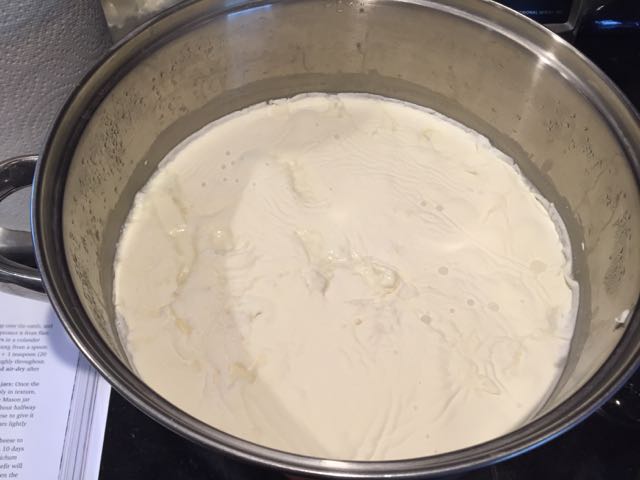

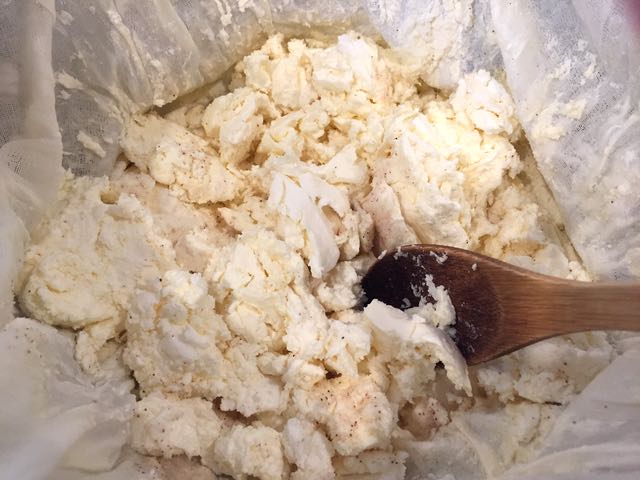

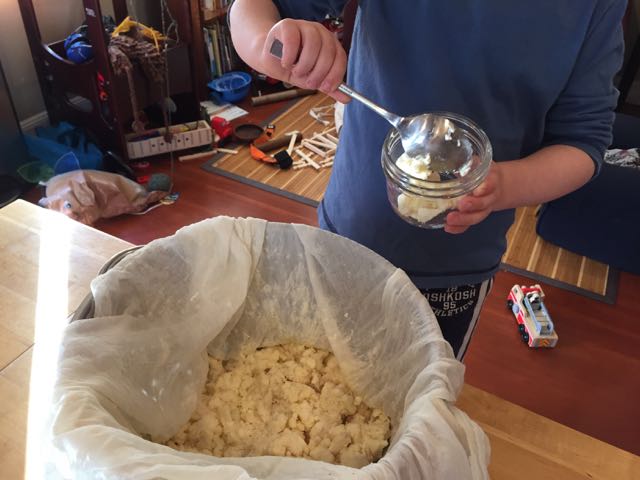

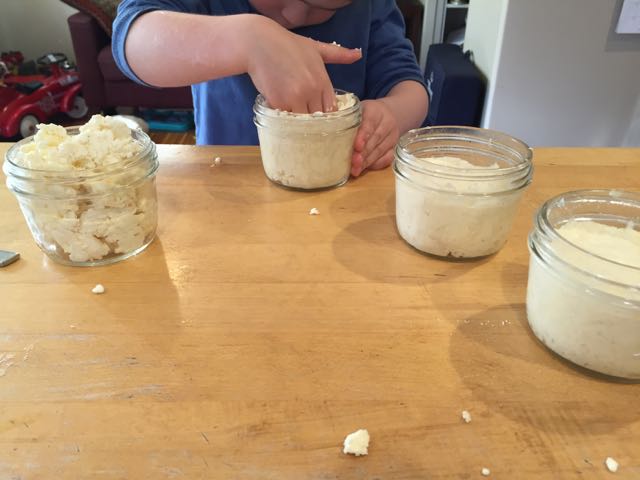

Saint Marcellin starts out like the feta and chèvre we have made, except for the obvious difference that it uses cow's milk instead of goat's. We took a gallon of raw cow's milk, heated it to baby-bottle warm, and added active kefir and rennet. We fermented it until Geotrichum candidum bloomed, and then we drained the curds. After a day of draining, we added salt, and then we let the curds drain for two more days.

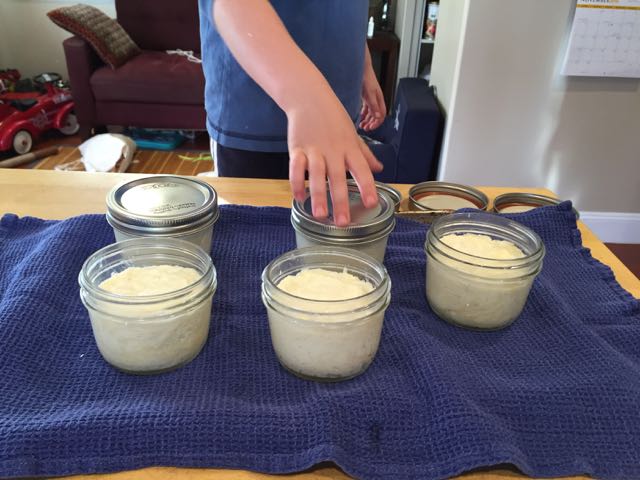

Once the curds had drained, it was time to pack them into jars. We sealed the jars loosely. On November 27, we placed the jars in our garage, where the temperature was about 60-65 degrees Fahrenheit. We opened and checked on the cheese daily. In ten days, we had an impressive coat of Geotrichum candidum on the surface of all the cheeses.

On December 7, we closed the jars tightly and stacked them in the refrigerator.

We check on them twice a week, wipe off any moisture on the lids, and place them back in the refrigerator.

Because the cheese should be ready in in four to eight weeks from December 7, and my parents were visiting over New Year's, we tried one of the jars on New Year's Day. Here's a photo of our cheese board:

In the back row, from left to right, we had: Dunbarton Blue, our very own Mason Jar Saint Marcellin, Fat Bottom Girl, and a lovely California Crottin. In the front row, from left to right, we had: our own homemade creamy feta, Jeff's Select Gouda, and Monte Enebro. We ate our cheese with homemade gluten-free sourdough bread, black eyed pea soup (with Super Lucky 2016 black eyed peas from Rancho Gordo), and Ethiopian-style collard greens.

The Saint Marcellin was still a little young, but it was already incredible. The top quarter inch or so of cheese had gone, as Wyatt said, "liquidy," and the rest of the cheese had begun to soften but still retained a sort of puffy, slightly granular texture. The "liquidy" section was the most delicious part--creamy like a ripe brie but with a bright, slightly sharp flavor. The rind was so thin and delicate, it was practically nonexistent. We ate the entire jar that evening. As the aging process continues, more and more of the cheese will liquify like the top layer of the jar we already enjoyed. We plan to let the remaining four jars of cheese age for another several weeks in the refrigerator, fully confident that the cheese will be worth the wait.

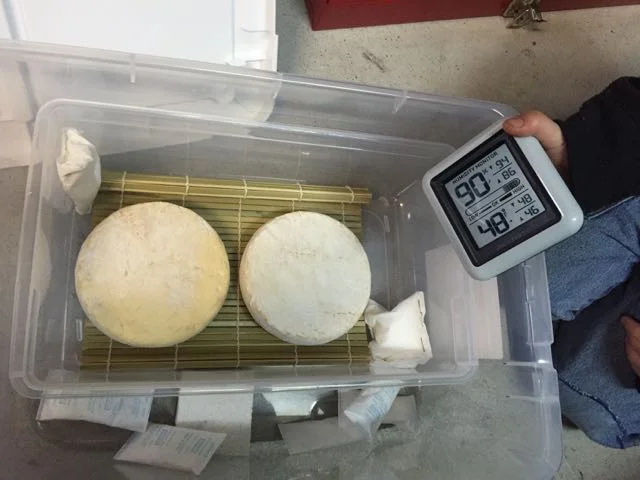

Meanwhile, we also have two separate cheese caves going in the garage. One is for Camembert that started aging on December 12, and one is for Crottins and Valençay cheeses. That one went into service yesterday.

And because you will never guess what we did with the last slice of sourdough bread from dinner on New Year's Day, I will tell you. We have inoculated it with a pea-sized piece of Cowgirl Creamery Rogue River Blue Cheese so we can grow our own Penicillium roqueforti mold and make our own blue cheese sometime soon.