Victorian House in the City

Lately, I have been knitting like it's my job. I am knitting Wyatt's Halloween costume this year, and I started later than I should have. I ordered my yarn at the end of September, which is too late for much measure of comfort in terms of an end of October deadline.

During the same time that I've been knitting up a storm, I've been reading Little House on the Prairie aloud to Wyatt at bedtime.* Hearing about the long wagon ride from the Big Woods out to the Prairie, how the family built their home and stable out of raw materials, and how they traveled and kept house in the wild has been absolutely riveting to him. For me, revisiting this story as a parent has given me new respect for every pioneer parent who ever lived. Life was hard.

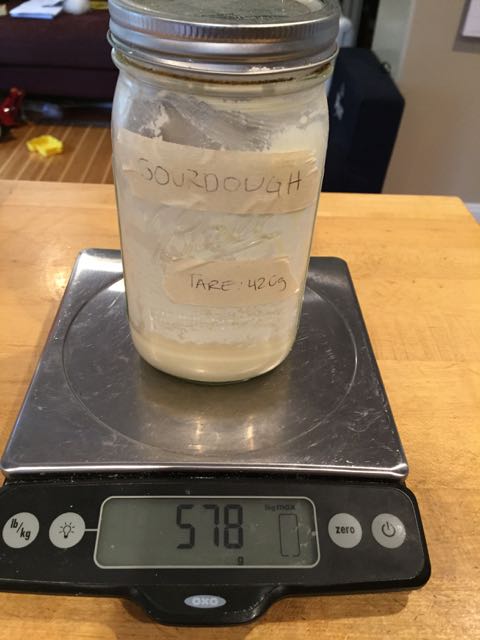

While Ma and Pa have been felling trees, building a house, cooking over an open fire every day, and ironing their clothes on a bed in their covered wagon,** I've been knitting a Union Suit pattern by Megan Grewal. I chose this pattern because it will work perfectly for Wyatt's costume, and because it involves several design features I've either never done or never mastered. For example, I've never knitted a garment with legs or a gusset, and I need to practice my buttonholes.

The yarn I am using is Balance, by O-Wool. I've been challenging myself over the last year to make more responsible choices when buying crafting materials, as well as when buying ready-to-wear clothing and home goods. O-Wool has terrific standards. Owner Jocelyn Tunney offers environmentally responsible, affordable yarn that is made in the United States from certified organic materials. Jocelyn also gave me excellent advice on which color yarn to purchase. I didn't feel like I had time to order a swatch card before actually ordering the yarn, so I emailed her and told her about my project. In my email, I included links to the general color of yarn I wanted to find, and I told her I thought that I should order Graphite, but I wanted to see what she thought. She confirmed that Graphite was the way to go, and it's absolutely perfect in person.

I have just found and ordered the buttons we will use. I think Wyatt will be able to help me paint them, which should be fun.

Wyatt checks every day to see my progress on his suit. He is starting to understand that knitting takes time (for me anyway). And he knows that when I finish the legs, I'll move on to the arms, then the butt flap, and then the button bands. His anticipation is great, and I love that he's gaining appreciation for the work that goes into creating things.

The other night, after I put Wyatt to bed, I sat grafting together the two halves of the gusset on the suit. That little patch connecting the two leg holes reminded me of the many pairs of store-bought tights I've worn, ripped, and thrown away in my life. I imagined having to sit and knit a pair of stockings because someone in my family absolutely needed them. And there would be so many other other garments everyone would need. Knitting was probably the easiest and most restful activity a pioneer homemaking woman would have during her exhausting day, and there would be so much of it to do.

Reading about the Ingalls family during a week of furious-knitting-by-choice has made me so grateful I live with modern conveniences. We have running water, electricity and a washing machine! And we get to choose whether to knit our sweaters and socks, sew our clothes and sheets, or hunt, grow and cook our own food. Modern life may be more complicated in some ways than pioneer life was. But I prefer the luxury of making choices about what to buy, what to make, and researching sustainable options over having to make everything myself.

*We had already read Little House in the Big Woods a few times and were ready to try another one in the series. When I read these books to Wyatt, I do some editing on the fly. I omit the scenes, songs, and references that are not appropriate for him right now.

**The ironing really gets me. Was this ironing out of pride? Or habit? Good, crisp Christian values, maybe? They saw no one else for days and days, and yet, Ma ironed everything. I feel like ironing would be the last thing I'd do if I were resettling, but maybe that's because I only iron when I absolutely have to.